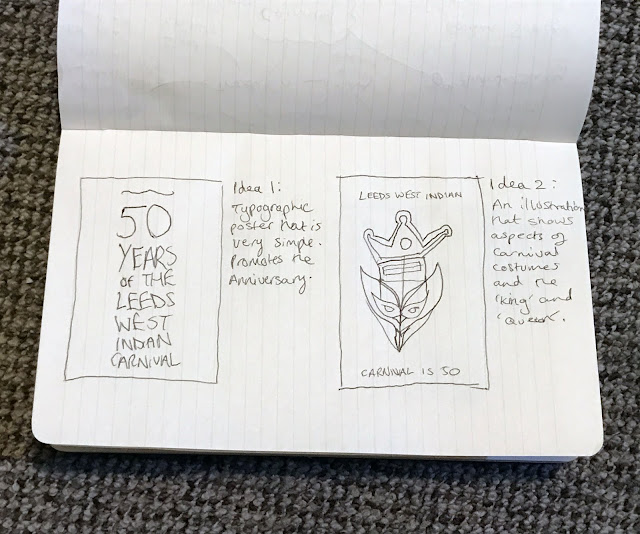

After researching into a variety of events I found Leeds Carnival to be the most significant, ongoing event that is celebrated. To find out about the history of the event and various cultural aspects I completed further research into the Carnival. Notes made can be read below.

Leeds Carnival Facts

Leeds Carnival Facts

- It is also known as Leeds West Indian Carnival or the Chapeltown Carnival.

- It is Europe’s longest running authentic Caribbean carnival parade.

- It attracts 100,000 people annually.

- It was started in 1967 as one man’s remedy for homesickness.

- This year (2017), it will be celebrating its 50th anniversary.

- It is held annually on the last Monday in August

History – Origins

Leeds West Indian Carnival began in 1966/67 with an idea of Arthur France, MBE, who settled in the UK in the late 1950s from the Caribbean island of St Kitts-Nevis.

In 1966, with 2 of Arthur’s friends: Frankie Davis from Trinidad, and Tony Lewis from Jamaica, both students in Leeds organised a carnival fete at Kitson College, Leeds (now Leeds City College of Technology). Ian Charles, originally from Trinidad, was also there.

The success of this carnival indoor fete inspired Arthur France to embark on the ambitious idea of organising a carnival parade through the Leeds streets, together with an indoor festival of music and costume.

Many people thought Arthur’s idea was crazy, but he persevered with his ambition, with the help and support of Ian, as well as from others including Calvin Beech, Willie Robinson, Samlal Singh and Rose McAllister. As a result of their efforts, Leeds Carnival hit the streets for the first time in 1967.

Arthur is still the Chair of the Carnival Committee, and Ian is the Treasurer.

Although there was a Caribbean carnival presence at the Notting Hill fair in London in 1966, which included West Indian people from all over Europe, in national costumes, the Leeds West Indian Carnival in 1967 was the first exclusive West Indian parade organised solely by British Caribbeans and composed mainly by black people in carnival costumes with Caribbean steel bands. Notting Hill street fair did not become a solely Caribbean style carnival until the early 1970s largely due to the success of the Leeds Carnival.

Arthur devotes much of his free time and energy to the Carnival every year, mainly because as a child in St Kitts-Nevis, brought up by strict religious parents, he was not allowed to participate in Carnival, largely due to the often inter-fighting between rival steel bands. However, he remained fascinated by the spectacle and sounds of Carnival. When he arrived in Leeds, this memory of his native land stayed with him, fuelling a dream of staging and recreating a Caribbean carnival in Leeds, thereby reminding him of Caribbean home. Arthur France has stated that on first hearing the St Christopher Steel Band in Potternewton Park with the pans around their necks he knew his dream had been fulfilled.

Celebration of Rights

Arthur France stated in 1994:

“Carnival also reminds us of our roots, the struggle our ancestors had to bear, the oppression of our leaders, and great role models, but not in vain, for while we continue to celebrate carnival their achievements well remain with us forever.”

The late Dr Geraldine Connor (ethnomusicologist and artistic director of Carnival Messiah) said in 2007:

“Carnival is not just a legalised rave – lest we forget, millions lost their lives in the pursuit of liberty. Today, Carnival best expresses the strategies that the people of the Caribbean and black British citizens have for speaking about themselves and their relationship with the world, their relationship with history, their relationship with tradition, their relationship with nature and their relationship with God. Carnival is the embodiment of their sense of being and purpose and its celebration is an essential and profoundly life-affirming gesture of a people.”

In Max Farrar and Geraldine Connor’s essay in August 2002 on Carnival in Leeds and London, UK: Making New Black British Subjectivities, and the Chapter on The UK Carnival: The Context of Racism, they assert that one aspect of that history is the anti-colonial struggles for independence in the islands of the English-speaking Caribbean (James 1985, Parry and Sherlock 1971, Richards 1989). Another is the experience of Carnival.

They assert that Carnival was created in Britain as one of the responses by black settlers to the “disenfranchisement, blatant racism and victimization they experienced in the 1950s and 1960s”.

They reference in their chapter Brian Alleyne (2002) (Radicals Against Race – Black Activists and Cultural Politics, Oxford and New York: Berg). They state that Brian Alleyne points out that the development of Carnival in Britain in terms of “a struggle by West Indians to make a public expression of a collective identity in the face of a structurally racist and hostile social reality in Britain. They have treated the carnival as one instance of the ongoing struggle of Black people to forge social and political space in Britain.”

In the conclusion of the chapter, Max Farrar and Geraldine Connor argue that “Carnival, which is normally non-confrontational, understands that the anti-human negativity of racism is effectively challenged by the embodied, human performance of art – an art that has been created “By the people, for the people”, which occupies and transforms public space.

Costumes

Costumes

According to Max Farrar, in his article in the Leeds West Indian Carnival Magazine’s 21st Anniversary 1988, Ian Charles, one of the original founders of the Carnival in 1967, was born in Trinidad and joined a Sailor Band, a Mas Camp, at the age of 16 years old, just after the Second World War, when he arrived at College in Port of Spain from his home town. Annually at Mas Camp, until he came to Great Britain in 1954, Ian learned all about costume-making.

According to Max Farrar, Arthur France, the main original founding member, stated that in his homeland of St Kitts-Nevis, Carnival is a smaller event, held annually at Christmas, unlike Trinidad, where Ian Charles was born, which is widely considered to be the home of Carnival, inspiring all the best carnival costume-makers all over the world.

The first carnival was memorable. Ian Charles was working away from Leeds as a survey engineer and would return home to find his home in Manor Drive turned into a Mas Camp, with three costumes being made inside, preventing his entry in both the front and back doors.

The other Mas Camp was at Simlal Singh’s home in Lunan Place. He designed and made the winning costume, the Sun Goddess, with Vickie Seal as his Queen.

Pre-Carnival History

The Carnival movement in Leeds began with two Trinidadian students, Frankie Davis and Tony Lewis, who organised a fete at Kitson College. They booked the famous Soul band “Jimmy James and the Vagabonds”.

Max reports that Arthur states that Marlene Samal Singh who later married Tyrone Ambrose organised a troupe of “Red Indians”, and that Frankie Davis got on a bus dressed in his costume to come to the fete. Arthur claims that his idea of establishing Caribbean culture and carnival in Leeds is traced back to this day of the fete.

Inspired with an idea to set up and organise his own Caribbean Carnival in Leeds, he decided to do some research with other resident West Indians in Leeds as to their thoughts on how they would feel about taking part in a Caribbean carnival here in the UK. Max quotes Arthur as saying that 80% of West Indians he talked to said that it would be degrading to take part in Carnival and that many people believed that the police would not allow a street carnival to take place.

Arthur had already, with over 22 others, formed the United Caribbean Association (UCA). Among other things, the UCA tried to work to address the political problems facing the black community and it developed cultural and educational activities, including the first Saturday school for black children.

Arthur approached the UCA members to sponsor the Carnival. Although they initially said no, Arthur was persistent in persuading and convincing every member individually to the positivity of endorsing a Carnival in Leeds.

First Carnival Procession

It left Potternewton Park and directly on to the Town Hall, where the first stell bank competition was held in front of a crowd of over 1000 people.

The Judge was Junior Telford, from London, who had brought his first Trinidadian steel band to Europe. The winning troupe was the Cheyenne Indians with Ian Charles as the Chief. Samlal Singh and Anson Shepherd organised a children’s band.

Junior Telford, along with 2 other Londoners, who had attended the Leeds Carnival took the news of the success of Leeds Carnival back to Notting Hill.

Recent Photos

Recent Photos